Cracker home design was uniquely suited to the local climate and these backwoods country settlers made use of abundant native forests of Southern Yellow Pine in their construction. Pine heartwood, now rare in the age of clearcutting and timber plantations, is virtually indestructable by pests or decay, and was used even for foundation blocks placed directly on the ground. This picture shows a typical cracker style house in north Florida. Notice the wrap-around porches and hip-style tin roof. In the back is a detached kitchen. The house sits on blocks about two feet off of the ground.

What is the climate of north Florida? About half of the year, from mid-April to mid-October is generally hot and humid. Daytime high temperatures are normally about 90 F and nighttime lows are in the low 70's during May through September, and slightly cooler in April and October. Mostly, the months from mid-February to mid-April and mid-October to late November are delightful, with cool nights and warm, but not hot, days, and low to moderate humidity. December and January can be cold, with several to about a dozen freezing spells.

Rainfall is more uniform throughout the year in northern Florida than in the south, and this has to do with the mechanism of rainfall. Cool season rainfall (meaning the 6 months from mid-October until mid-April), from 2" to 4" per month, comes from advancing cold fronts, which weaken as they move south. During the hot months, the land heats up as the day advances, causing the humid air mass over the land to rise. This brings in air from the ocean and Gulf, a so-called sea breeze. As the moist air rises, it encounters lower pressure and expands, which causes the air to cool. Because cooler air can hold less water, moisture condenses to form clouds and eventually, rain. This "convective rain" is more commonplace in southern Florida, where the sun is more intense. In northern Florida the average rainfall is about 7" per month during June, July and August. Rainfall in the summer is highly variable. We have been recording rainfall at our house for the last five years, and logged 21" in June of 1994, with 1" for May of 1993! The windspeed is generally low in the central peninsula. It is too far inland for a substantial sea breeze, and except for short-lived storms or an occasional hurricane in the area, winds are normally from still to 8 mph.

In researching passive solar design, we found that most available books and references consider primarily (or only) solar heating, whereas we were almost entirely concerned with passive features to enhance cooling. An excellent resource that we found for passive solar design in hot, humid climates is the Florida Solar Energy Center. The FSEC is the energy research institute of the State of Florida. The center is nationally recognized for comprehensive programs in solar energy and energy efficiency and is administered by the University of Central Florida. Numerous publications and pamphlets are available through FSEC for a very small fee. Also, their Building Design Assistance Center (BDAC) offers free design assistance (which we have taken advantage of). Another resource that had a large influence on the design of our house was a book by University of Florida Professor Ronald W. Haase entitled "Classic Cracker - Florida's wood-frame vernacular architecture". In particular, a design featured in that book by architect Edward J. Seibert, was the inspiration for our house.

The example above does not consider the increase in temperature and water

content of the air caused by human occupants, opening doors, etc. Also,

the comfort zones refer to people sitting at rest, and someone sweeping

the floor may not be comfortable in those conditions. Also, fans are not

considered passive devices, although their power consumption (typically

about 50 Watts for a ceiling fan) is tiny

compared to an air conditioner. Still, the example serves to point out some

important principles. First, a house should be designed so it is easy to

exchange the inside

air for outside air when the conditions are right. Large, open rooms

with a minimum of walls, ceilings that slope upward with ventiliation

at the top, and vents near the floor facilitate this. Second, sources of

water vapor and heat should, as much as possible, be located outside of

the living area. Boiling water on the stove, or a shower can fill the

house with warm water vapor, which takes much energy to remove. Third,

the house should be leak tight. Sliding doors and windows, electrical

outlets, and ducts can be large sources of air leaks. If conditions in

the house become uncomfortable, it is important to be able to draw in air

from outside that is as cool as possible. Again, having a vent near the

floor surrounded by a large, shaded area is very helpful.

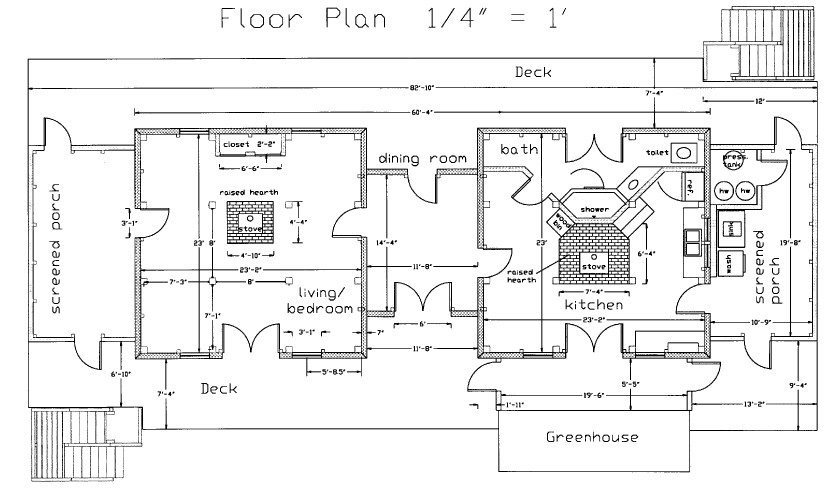

It is clear from the floorplan and from the isometric drawing shown on

the Florida Solar Cracker

House page, that the

house is divided into three units. At the east and west ends are the

kitchen/bathroom and livingroom/bedroom, respectively, and these units

are joined by a room in the middle, labeled dining room. The intent of

the "dining room" was to act as the breezeway of the traditional dog-trot

houseform described by Haase and seen in many early Florida cracker

homes. The function of this breezeway in our house will be to isolate

the part of the house where heat and water vapor are generated (kitchen

and bath) from the "living quarters" during the hot months, another

characteristic of the traditional cracker house. Our house, as built,

differs from the drawing here in that there are no doors on the north or

south sides of the dining room area, but, instead, large, 6 foot wide,

casement windows on each side. In addition, the connection to the kitchen

area is 8 feet wide and completely open, with no doors. The rationale for

these changes was to save money spent on expensive doors and to provide more

inside space in the house. Thus, our house, as built, is somewhat less like

the traditional cracker dog-trot house, but functionally, the dining room

still serves to isolate the hot, humid kitchen and bath areas from the

remaining living space.

The first picture above is a view from just inside the bedroom, looking

through the breezeway into the kitchen. Randy can be seen through the

kitchen door on the east porch. The second picture is a closer

view of

the kitchen from just inside the breezeway. Note the open structure, high

ceilings (the lowest points of the rafters are about 10 feet above

the floor) and

sloped ceiling with no attic. Ceiling fans draw hot, humid

air up into the cupolas and out through the cupola windows. The wall to

the left in the pictures is the wall enclosing the bathroom, but

notice that the wall only goes up about 9 feet, and the bathroom is open

above, with no ceiling. A ceiling fan is directly above the shower,

rotating so that air blows up in the summer, drawing humid air out of the

house. In winter, this fan blows air down, bringing warm air from above

the woodstove into the bathroom.

This is a view of the other ceiling

fan in the kitchen, showing the structure of the kitchen

cupola. Please click here to see some more pictures of the kitchen.

Outside the house, covering the entire east and west walls, are screened

porches. This next picture is a view standing on the west porch,

looking south. Boll Green Lake is only 200 feet from the house, but is

barely visible, due to thick vegetation.

Typically, east and west-facing walls are

difficult to shade because of the large range of sun angles they are exposed

to during the day. A good solution is to cover these walls with porches.

The south-facing wall is easier to shade with roof overhangs, because, in the

summer, the sun is always at a high angle to the south walls.

Part of the south side of the house will be shaded by

the greenhouse (not yet built), which will have internal shades on the

glass. How the roof overhang works to shade the south walls and the

importance of shading the walls in

preventing heat conduction into the house will be discussed in roof and wall

design in the next section.

The foundation of the

house consists of two concrete slabs, 36'x36',

with concrete block pillars supporting the subfloor. The floor is about 9'

above grade. The reasons for the elevation are several. First, the 100

year floodplane is about 4' above grade at the house site, and code

requires (wisely) that the first floor be above that level. Once the

house has to be up 4', one might as well raise it a few more feet, and make

usable space below the house. This is a good idea for ventilation

purposes, and makes for a nice view of the lake 200' away and the

surrounding forest. The concrete slab and pillars, which are filled with

concrete, provide for a substantial thermal mass below the house. We

will experiment with partially closing off this area, so that cool air

can be drawn into the house from this "basement".

The two-story greenhouse will share a wall with the cistern, which provides

a temperature-moderating thermal mass. The greenhouse will provide passive

solar heating in the winter, being open to the kitchen, but the

most important function of the greenhouse will be for food

production. Along

with a 2500 square foot organic garden, and many native perennial fruit

trees, we hope the greenhouse will help

us produce a large portion of the food we eat. We are no longer

vegetarians, and have begun to include some wild caught fish and some

locally and

humainly produced meats and dairy products into our diet. However, we

have maintained a simple diet as free as possible from processed foods,

and we think it is a realistic goal to

produce much of our own foods. The

greenhouse should allow us to grow more foods over winter, and start

seedlings

early for the main garden. This is a picture of Liz with a harvest from

our winter (outside) garden taken in February of 2004.

Basic Psychrometrics

Psychrometric charts show in a simple graphical form the state of an air

mass in terms of its water content, temperature and energy. They can be

invaluable in helping to understand how to passively cool a house. Most

people understand that hot air can hold more moisture than cold air, but

from a psychrometric chart, one can predict exactly how the relative

humidity (RH) of

the air in a closed room will decrease if its temperature increases. For

example, suppose the outside temperature and relative humidity at 6 am

are 70 F and 100%, respectively, (typical summertime overnight

conditions in north Florida). Let's assume the air inside of your house is

in the same condition as the outside air because the house has been

well-ventilated overnight. Now, you shut the windows and capture that

air in an leak-free house. As the day wears on and the outside

conditions deterioriate to 90 F and 90% RH (also typical conditions in

north Florida), let's say the air temperature inside the house rises to

80 F due to heat conduction through the walls and roof. The

psychrometric chart tells you that the RH of the air at that point has

fallen to about 72%. Statistical studies of human comfort have been

performed that indicate certain zones of temperature

and RH in which most people feel comfortable. In our example above, 80 F

and 72% RH is outside the comfort zone if the air is still. However,

even in moderate airflow, such as that provided by a ceiling fan, those

conditions would be well within the comfort zone. Thus, by simply

manipulating ventilation and airflow, and minimizing the introduction of

heat and water into the house, the house can be kept comfortable.Overall Layout

The CAD drawing

below shows the floor plan for our house.

Structure and frame

This picture shows the frame of the house as it was going up. The

construction is post and beam style, but without the mortise and tenon

joints. We opted for bolted connections on the timbers, for ease and

simplicity of construction. All of the framing members you see in this

picture, except for the

rafters that extend beyond the walls, which support the overhanging roof,

are

visible inside the finished house. The walls and ceiling are entirely

outside the frame, and in the upper left, you can see the ceiling deck being

screwed in place on top of the rafters. All wood used in the house, except

the plywood subfloor was cut by us on our sawmill, as described in the

section on

Green Building

This picture shows the frame of the house as it was going up. The

construction is post and beam style, but without the mortise and tenon

joints. We opted for bolted connections on the timbers, for ease and

simplicity of construction. All of the framing members you see in this

picture, except for the

rafters that extend beyond the walls, which support the overhanging roof,

are

visible inside the finished house. The walls and ceiling are entirely

outside the frame, and in the upper left, you can see the ceiling deck being

screwed in place on top of the rafters. All wood used in the house, except

the plywood subfloor was cut by us on our sawmill, as described in the

section on

Green Building

Roof and wall design

Doors and windows